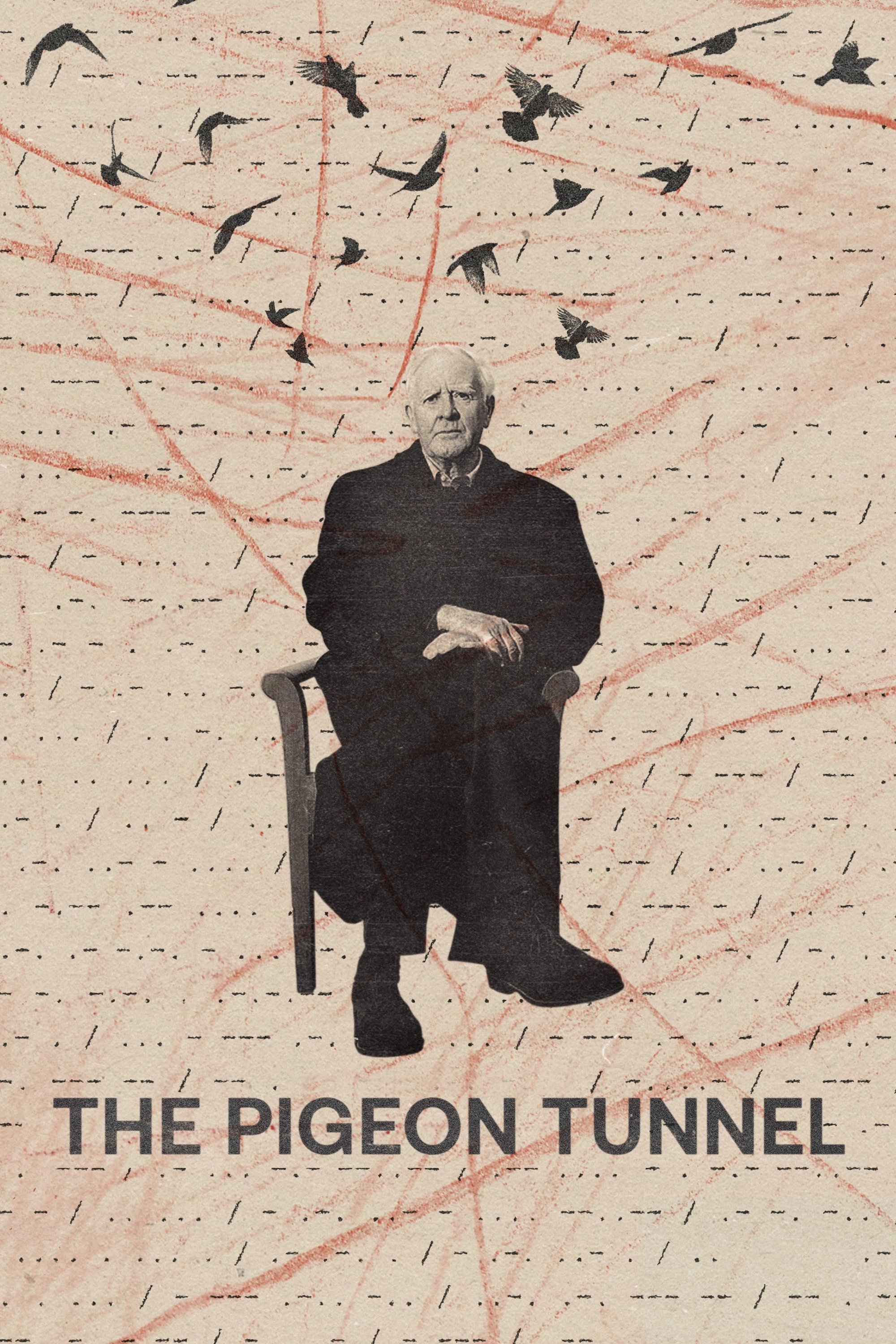

The Pigeon Tunnel

I knew three things about this movie going into it: it was about le Carré, it was by Errol Morris—who I hold in very high esteem via The Fog of War, which I would describe as a strongly interrogative film—and that it too is deeply and highly regarded. These three facts lend you to some suppositions about what this film could be. And in a certain sense, my assumptions were correct. This is very much a deconstruction of le Carré's psyche and an earnest attempt to understand a man who towers over a genre in no small part due to his enigmatic personality.

But this is a very soft film. Both subjects make repeated references, oblique and explicit, to the combative nature of the interviewing process and draw parallels to the process of interrogating a prisoner—as so often depicted in le Carré's work—but you also get a sense that one or both parties involved agreed from the onset that the gloves were not going to come off. Morris is chiefly concerned with a single aspect of le Carré's background: his relationship with his father. The film explores that relationship and how it influenced the writer's worldview in all respects—loyalty, honesty, success.

This is a beautiful film, almost hedonistic in its pleasures relative to the gravity and seriousness of the subject being discussed. But I do not come away from it with a newfound appreciation for le Carré himself, nor the genre that even now—five years after his death and many decades after his heyday—he pioneered and won.

There are a couple possible reasons for this. One, as always, is metafiction. You could probably spin a great take about how this documentary itself, like the memoir sharing its name, is an instance of le Carré giving up the short con to set up the long. What he discusses is meant to be redirection rather than reckoning. I don't really buy that, at least for me. I think le Carré is like Agatha Christie: a perfect writer who knows exactly what they're attempting to do and succeeds time and time again in doing it. But I do also not delude myself into thinking that any of this writing is meant to be more than fiction, nor that it has to be in order to contain truth.

This film is interwoven with various public clips of le Carré—under his true name, David Cornwell—appearing in talk shows and various public outlets, demasking the man over his decades-long career. It is exciting to pretend, as he suggests in the closing minutes of the film, that there is a deeper vault hidden within the deepest. In reality, there is rarely ever a vault, if even a room. This is what we've got, and we should appreciate it.