Befriending the Goon Squad

TL;DR

- The single biggest asset that side projects and "nights and weekends" businesses have on their side is near-infinite runway.

- If you have near-infinite runway, your largest risk is yourself: you get bored, you get demotivated, you get distracted, etc.

- If you're sufficiently patient and disciplined, you can wait out the competition and rely on slow, compounding growth.

- This doesn't work forever, but "five years of slow growth" is often the difference between a side project and a lifestyle business.

A Visit From The Goon Squad

Time’s a goon, right? You gonna let that goon push you around?”

Scotty shook his head. “The goon won.

A service I admire a lot is blot.im, a headless CMS of sorts — you provide a list of files, connect Dropbox/Git/etc., and it turns it into a full blog (or portfolio, or reference, or whatever.)

Blot's about page contains a list of alternatives, a move I think is always equal parts kind and useful, but with a bit of a twist:

More dead competitors than alive.

I've chatted with David, who runs Blot, a few times; I've never quite asked him how explicit the intent of this section is. Is it a warning? A boast? A bit of both?

To me, it sends a clear message: there are many competitors that have come before; there will be many that follow; despite that all, Blot remains.

This is an important message for independent developers to internalize: especially in crowded markets, survival, not victory, is the success condition.

I run Buttondown, a newsletter platform. Buttondown shares very little with Blot, but they are both in very crowded spaces — awash with competitors, some of whom are amateurish, some of whom are quite well-funded.

I've been asked many times some variation of the question "how do you deal with the competition?" There are many answers to this question; in this essay, I want to give one: wait until they die.

Buttondown's first year

I launched Buttondown in the summer of 2017. The time seemed ripe: the New York Times was writing thinkpieces about the "email newsletter renaissance", and the tool du jour was not just bad but was actively deprecated.

Unfortunately, I am not a terribly unique person. By my count, eight other newsletter platforms launched in the same year as Buttondown, most of which were either VC-backed or had a significant amount of press coverage.

This was extremely discouraging. I was a solo founder, working on nights and weekends, with no funding and no real marketing budget, fighting for every new user. Seeing a glossy Verge write-up or a handshake Twitter integration felt viscerally painful

in a way that was both unactionable and paralyzing.

This puff piece was published literally one week after I launched Buttondown. Devastating!

Also in 2021, Revue — which launched shortly after Buttondown — was acquired by Twitter. I was fairly terrified at the prospect of Twitter deeply embedding a newsletter and long-form creation into their tooling; they unceremonially shuttered their business in early 2023.

Facebook Bulletin, a newsletter platform, launched in 2021. It lasted less than two full years.

How to make time your ally

In reality — many of these services lacked staying power. Two of them were shuttered by freelancers who got bored; one was quickly acquihired and succumbed to bitrot; others scuttled along in various degrees of non-success.

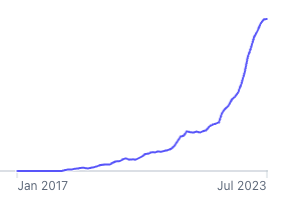

Buttondown, meanwhile was growing. Slowly, slowly, it grew, customer by paying customer. It had time on its side: I had zero burn, it wasn't my full time job (and thus I didn't need to pay myself), and I had no investors to answer to.

Moreover, many of the things functions that Buttondown relied on (word of mouth marketing; beneficial unit cost economics that come from SMTP; SEO juice) all benefited from wall clock time.

Five years passed. I hacked on the product with a dogged sense of preserverance and faith. Some months were "good months" (no churns, two paid new users); some months were good months (competitor shuts down).

There was no big bang; there was no moment of arrival. You sit, and wait, and water your garden every morning; one day, you wake up and discover a farm.

"A farm", in my case, was a business that in its first year felt stuck at sub-$500 MRR that now was large enough and stable enough to support me full-time.

Plateaus versus finish line

This approach works — to an extent. Time will help your organic growth and cull weaker competitors from the fold, but it won't magically solve significant gaps

in your product's feature set or fundamental flaws in your acquisition and retention model.

After a certain point in time, the diminishing returns of "just let it sit" will be indistinguishable from zero, and you'll have a product in some sort of terminal state.

What to do with that terminal state depends on your relationship with the product:

- If it's humming along at a relatively small scale and you have no real desire to grow it, then congratulations! You've built a lifestyle business.

- If it's humming along at a relatively small scale and you do have a desire to grow it, then you're going to have to start investing time and energy into it again. Maybe the "nights and weekends" is no longer enough; maybe you need to start hiring and/or working on it yourself.

- If the hum is either too quiet or altogether absent, then it's time to call the thing a failure.

I chose the middle path: torn between keeping Buttondown in a level of suspended animation and rolling up my sleeves to work on it full-time and break through to the next level of success, I chose the latter.

It has gone pretty well thus far.

Via negativa

There are entire swaths of project for which this approach is not applicable. If the project you're working on:

- requires a very large amount of up-front capital and/or energy

- requires constant maintenance and/or upkeep even if well-architected

- is unappealing to you in the long term

- does not lend itself to organic growth

- cannot be indefinitely maintained alongside your current lifestyle and workload

- is not obviously monetizable

then this approach is not for you.

However! Inverting that list of criteria is a good way to find projects that do lend themselves to this approach. If you're looking for a side project, I'd recommend looking for projects that:

- Require little up-front capital and energy

- Can be maintained with minimal upkeep

- Are appealing to you as a decades-long project

- Lend themselves to organic growth

- Can be indefinitely maintained alongside your current lifestyle and workload

- Has already been monetized and validated in some way

If you find an idea that checks all of those boxes, then you have yourself a project

whose greatest risk for failure is you: you get bored, you get demotivated, you get distracted,

you get busy. Apply enough rigor, discipline, and patience, and you can find yourself hacking on your life's work.

Have ye a yeoman's heart?

Most of this work is unglamorous; much of it is unfulfilling. (Anyone who suggests otherwise is probably more interested in selling you something than steering you in the right direction.)

I spent five years waiting and working and, in a very priviliged sense, sacrificing:

- nights and weekends are spent debugging edge cases with role-based access control instead of bar-hopping with friends;

- my hourly compensation was a fraction (not a small fraction, but a fraction!) of what you could be making at a FAANG or a post-PMF startup;

- energy working on things that are solved problems instead of doing interesting engineering.

- a truly terrible PagerDuty rotation (as in, there was no rotation, there was only me).

In exchange, I reaped:

- a deep sense of ownership and pride over my work;

- a level of freedom and agency impossible in a traditional job;

- a calendar that contains only the meetings I wish it to.

This may be an uninteresting trade for you; for me, it brought me to the happiest place I've ever been in my career.

Postscript (I)

To close out this essay, I'd like to bring up perhaps the most famous example of this working in practice: Pinboard's 2017 acquisition of Delicious,

which was something of a watershed moment in the niche indie software community of that era. (800 points on Hacker News!):

As for the ultimate fate of the site, I'll have more to say about that soon. Delicious has over a billion bookmarks and is a fascinating piece of web history. Even Yahoo, for whom mismanagement is usually effortless, had to work hard to keep Delicious down. I bought it in part so it wouldn’t disappear from the web.

This is the fifth time Delicious has been sold. Founded in 2003, the site received funding from Union Square Ventures in 2005, and sold to Yahoo later that year for somewhere between $15-$30M. In December of 2010, Yahoo announced it was ‘sunsetting’ Delicious, an adventure I wrote about at length. The site was sold to the YouTube founders in 2011. They subsequently sold it to Science, Inc. in 2014. Science sold it to Delicious Media in 2016, and last month Delicious Media sold it to me.

Do not attempt to compete with Pinboard.

Flash forward six years, and Pinboard appears to be on death's door; the last post is from 2020, a year which marked three consecutive years of revenue decline. HN posts so many essays complaining about its stagnation that it has become a bit of a cliche unto itself. And successor technologies — Anybox, Raindrop, and so on.

"Live forever" lacks infinite viability; you cannot in good faith be perfectly confident that the you of a dozen years from now maintains the rigor and excitement and wherewithal to water and lovingly tend to the seedlings you plant today.

And yet. That's no reason not to try.

Postscript (II)

In the three week chasm between my starting and finishing this essay, one of Buttondown's competitors raised $12.5 million.

I am excited to revisit this writing in 2033.

Postscript (III)

Thank you to:

- Haley and Shep for reading drafts of this essay, and more importantly for carrying me through the months in which my patience was tested.

- Iheanyi, Buttondown's original hype man and de facto CTO, for keeping me from making too many terrible architectural decisions in those early years.

- Everyone who signed up for Buttondown back in those 2018—2019 days, who suffered and stuck through some truly terrible settings interfaces. You all will always be my favorites.