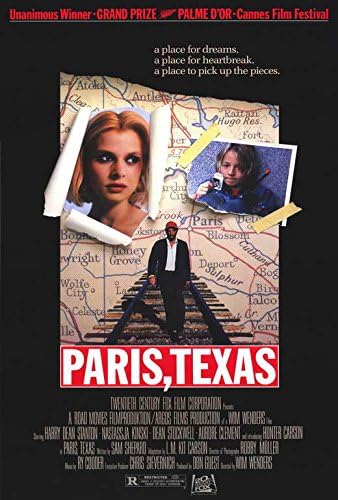

Paris, Texas

WWS_w1600.jpg)

Why is it that the more I love a movie, the harder I find talking about it?

Perhaps it's because my favorite movies are either rich texts through which I spend much time turning things over and retracing steps (synecdoche-new-york, my-dinner-with-andre) or are so fully realized that I find myself without much to say besides "gee, this sure is great" (rear-window, before-sunrise). It is easier and more rewarding to write about flaws, even flaws in things I liked quite a bit.

If you've seen Paris, Texas you know it falls in the former bucket. There is not much mystery in the text left by the end of the film, but the vividness of its world sticks with you: I am now, a week later, still thinking about the last time we see Aurore Clément's character — or the languid heat of the bank "stakeout" — or the initial descent into the underworld of the peep show club.

Wenders wrote that he wanted this to be a film about America, and certainly the film invites itself to be read as a commentary on the American Western. But I think its lineage extends further back, into Greek myth: American Westerns—postmodern or otherwise—are stories of the individual. Greek myth, by contrast, is about family and inheritance: Aeneas founding a nation, Odysseus finally coming home.

This film is most interested in uneasily and deliberately straddling the divide of those traditions. Harry Dean Stanton's character is a bad person to whom we grow sympathetic: he abused the bottle, he abused his wife, he stole away his son from any semblance of stability. Odysseus slept with Calypso for seven years; he murdered his maidservants for the sin of their having been raped by suitors; his arrogance led to the slaughter of his men.

Both men quested first for salvation and then for homecoming; upon the latter, they discovered the former was still some ways away. Not to be too on the nose, but both texts even involve convincing a wife of identity by telling a story nobody else would know. The Odyssey ends with divine intervention; Stanton's character is not so lucky. His nostos continues.

drive-my-car is one of my favorite movies ever, and despite that I can't remember much of the first half because it was so completely obliterated by everything the film built to in its final scene.

I could say the same about Paris, Texas. I will be thinking about those final fifteen minutes — the twin monologues, the hotel room, the world's saddest instance of driving off into the sunset — for a very long time; I will be thinking about the pink sweater and the black dress, the motherhood of burning down your house to save your son.