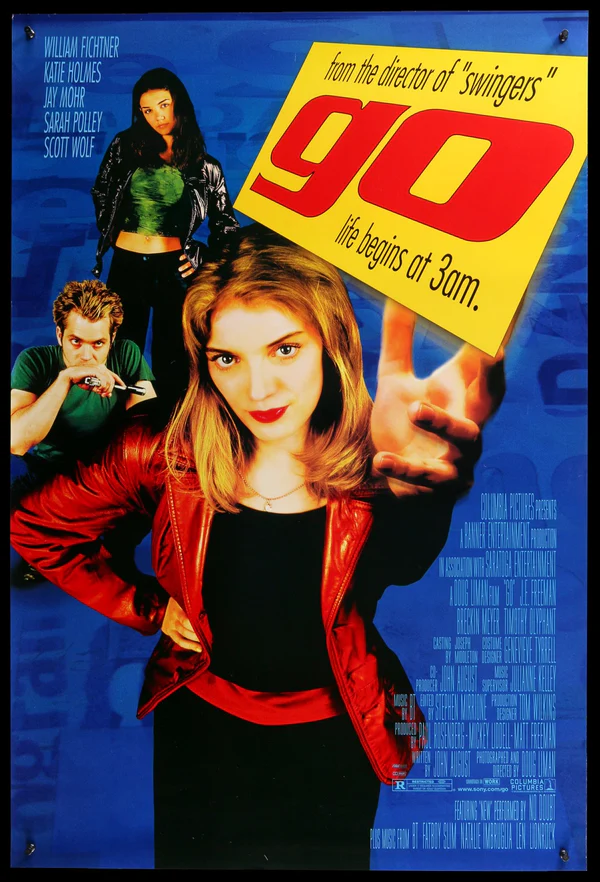

Go

You know what wakes me up in the middle of the night covered in a cold sweat? Knowing that you aren't any worse than anyone else in your whole screwed up generation. In the old days, you know how you got to the top? Huh? By being better than the guy ahead of you. How do you people get to the top? By being so fucking incompetent, that the guy ahead of you can't do his job, so he falls on his ass and congratulations, you are now on top. And now the top is down here, it used to be up here... and you don't even know the fucking difference.

I have never really been a big Tarantino guy. I think part of the reason is that a fundamental appeal of his filmmaking is mania—the sense of having your foot on the accelerator while slowly, slowly, slowly taking your hands off the wheel, just seeing what happens. I get that appeal, but my favorite movies tend more toward maniacal control and execution, where watching the film feels akin to observing a Swiss watch: a hundred parts ticking away in unison.

When Go first came out, its textual similarities to Pulp Fiction consigned it to a history of Tarantino comparisons, and even a good film in Tarantino's shadow seems diminutive by comparison. But the script here is fairly controlled, even if the characters within it are very much not. You get the satisfying experience of watching twenty different balls thrown into the air and, if not exactly deftly, having them all come back down in one piece.

After a relatively sleepy, Clerks-esque opening ten minutes, the movie throws you into acceleration and does not stop until the final shots. To that extent, it really does capture the feeling of a hedonistic night out in your early twenties—the surreal sense of not quite knowing how you ended up where you are.

What also helps is the film's unwillingness, unlike many Tarantino films, to sell any of its characters short. To me, the single most surprising twist—even if you couldn't quite call it a twist—comes in a moment that would be a throwaway in other films: the British character shooting the security guard in the arm. Rather than writing off that guard, never to be referenced or thought about or empathized with again, the film treats him as a real person, who has a father who is a real person, and that choice to explore them pushes the film forward and forward and forward in a way that feels more naturalistic than bombastic.

What else? The performances, from fresh-faced versions of folks we now consider mainstays: most of whom are more interesting than they are good. It's fun to see so many of these actors so early in their careers, still figuring out their voices. Sarah Polley doesn't quite sell it, but she works as an audience proxy if nothing else.