The start

I would be lying to you if I told you I remember exactly what was going on when I came up with the idea for Spoonbill.

I know I was still in what I would call my "year in the wilderness" — in a not-so-great relationship, in a not-so-great job, trying to compensate for both by moonlighting on a bunch of projects and drinking too many Manhattans. I do not mean this to sound dramatic, but working sixteen hour days is not good for you, and much of the artifacts of those years — even good ones, like Spoonbill — are slightly hard to trace back to their origin.

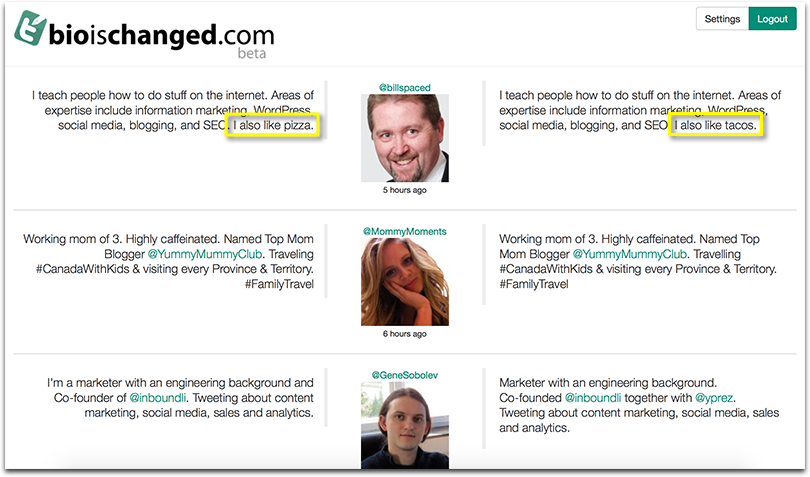

I remember this: at some point I stumbled upon a site entitled "Bio is Changed", which did exactly what you might expect: it was a big vertical feed of people whose bio had changed on Twitter. Most notably, I stumbled upon it from someone complaining that it was "going away" — the creators no longer wished to maintain it, and it would be slowly going the way of many other bitrot platforms.

Bioischanged.com was not exactly a well-designed app, which tends to be a good heuristic that it did something of value.

Bioischanged.com was not exactly a well-designed app, which tends to be a good heuristic that it did something of value.

I am not a particularly original person when it comes to interesting projects — I have found that the most successful process is something along the lines of:

- Find a tool that people clearly like despite massive flaws.

- Build a better version of it.

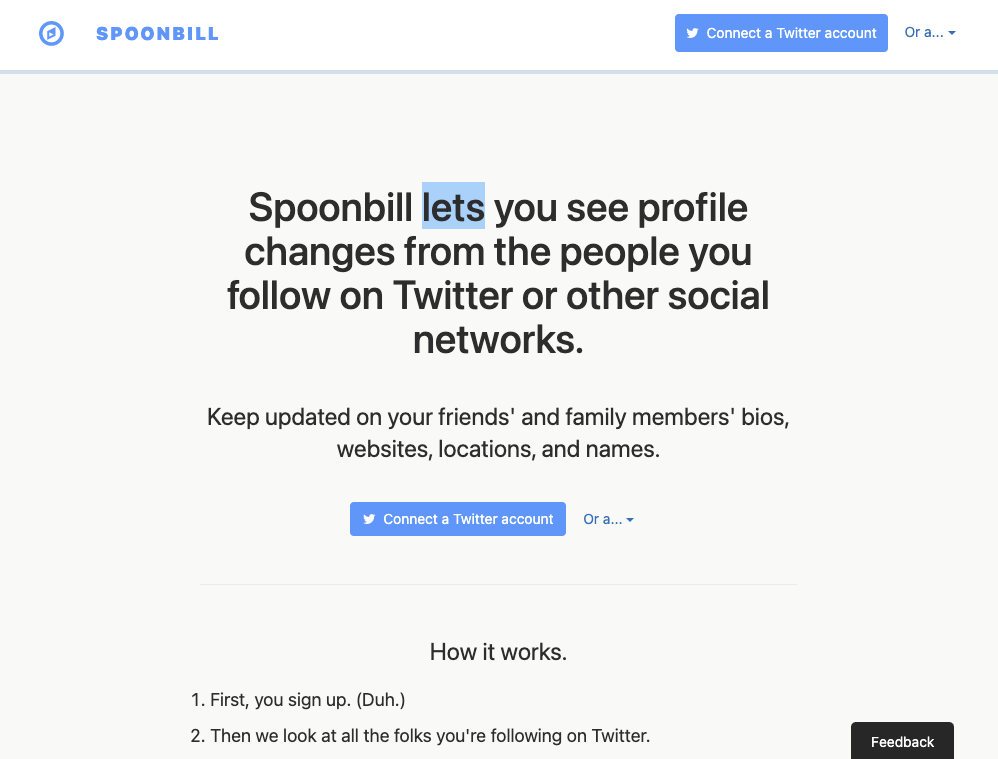

And so, I dedicated the next few weekends to building Spoonbill.

A testament to how little I've thought about Spoonbill in the past three years: I did not realize there was a feedback widget on the site.

A testament to how little I've thought about Spoonbill in the past three years: I did not realize there was a feedback widget on the site.

The stack (briefly)

I cannot emphasize enough how little the stack mattered, but: Django, Postgres, Heroku, and a labyrinth of cron jobs. None of these things changed over Spoonbill's existence: I worked with the tools with which I was most comfortable, and they all worked well enough to not require replacement.

The launch

One of the nice things about Spoonbill's being birthed from the ashes of a defunct product is that I had a bit of a built-in marketing funnel:

- Wait for someone to tweet about BioIsChanged shutting down.

- Reply to them with a link to Spoonbill.

This worked surprisingly well, especially because most of the folks in step one were in the journalism/VC/thought-leader-y space. A few weeks after launch, Spoonbill had met my relatively meager success criteria: a thousand or so folks were using it, people seemed to like it, and the Heroku bill was only $20 or so.

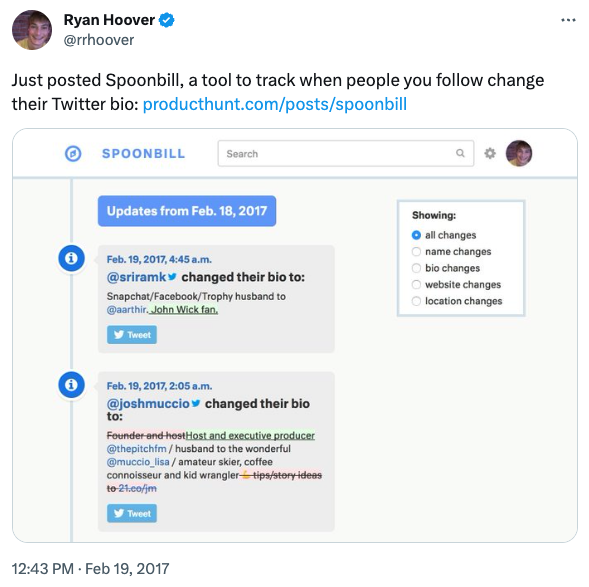

Then Ryan Hoover posted it on Product Hunt and things got a bit more interesting.

The 'hunt', such as it was, only made it to #5 or so but user count quintupled overnight and the ball was officially rolling, leading to what is even now, the best launch and series of reactions I've ever had. People loved Spoonbill.

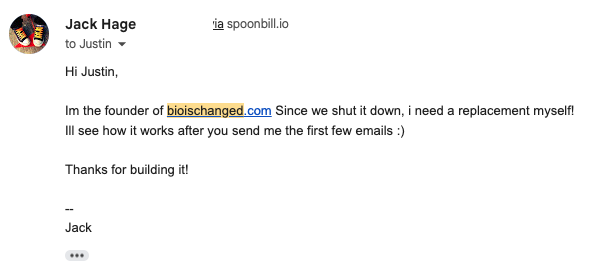

I heard from the founder of BioIsChanged:

No greater endorsement than that from the founder of the product which inspired yours.

No greater endorsement than that from the founder of the product which inspired yours.

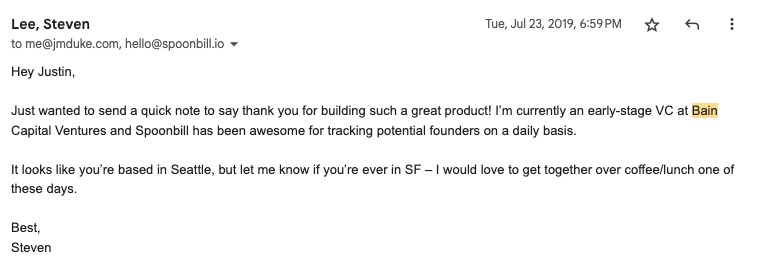

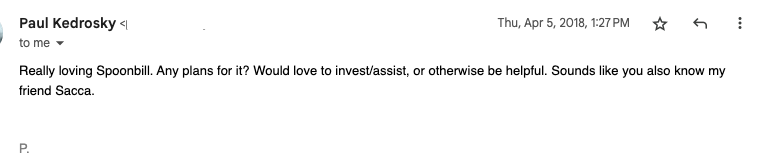

I heard from no small number of VC firms interested in learning more:

This genre of email was both common and surreal.

This genre of email was both common and surreal.

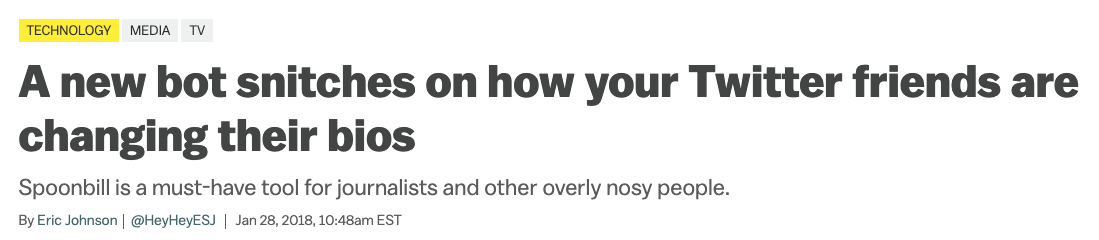

I got written up in a bunch of places:

Vox.

Vox.

All SEO is good SEO, as the adage goes.

All SEO is good SEO, as the adage goes.

It felt really, really good. When I think back to my greatest moment — or series of moments — as a software developer, this might have been it: the sheer endorphic bliss of having clearly and obviously built something that folks loved.

The money

If you're following along, you might have two questions right about now.

- "So you built a free tool? How did you make money?"

- "Wait, what happens if Twitter just shuts you down?"

For the first few months, the latter answer — nothing, Spoonbill is screwed — informed the former. I didn't really think that much about monetization, not because I didn't think Spoonbill was valuable but because first and foremost I wanted to make sure it would just stay alive.

Once it was clear that Spoonbill was not going to be arbitrarily axed by Twitter (my flimsy rationale for which being "multiple executives at Twitter, as well as people running the developer relations team, were all active users") I felt a little bit more comfortable thinking about monetization.

I settled on two main paths.

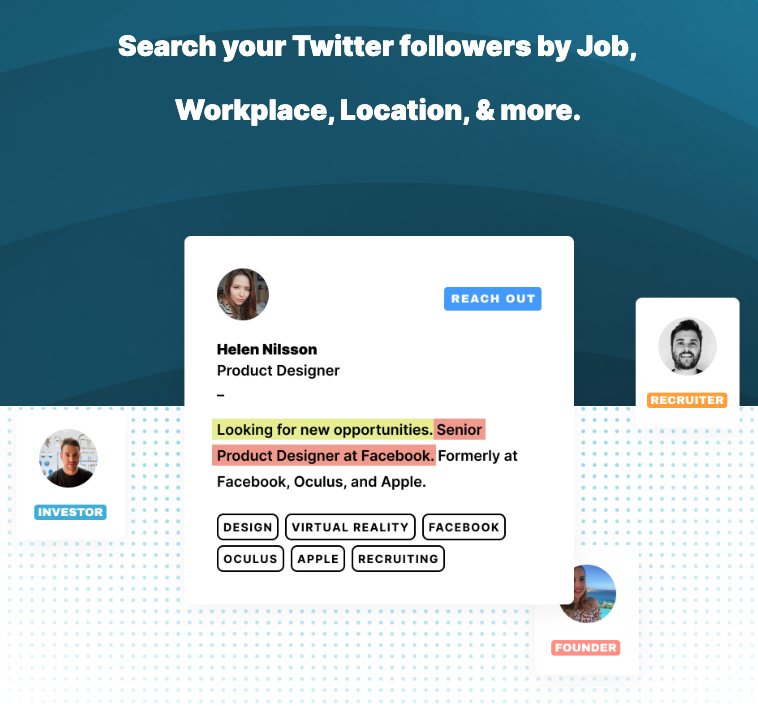

The first one was an amuse-bouche, a way to validate if people actually cared about this information enough to charge for it. I got a few customers, but I really didn't iterate on the product enough to find product-market fit.

The reason why I didn't iterate on the first path enough was because I realized just how much I could charge for the second path.

Figure out what number you can say to them without laughing. That's your price. Josh Puckett

I did this — twice! — and managed to sell a firehose of Spoonbill data to two separate firms: one for $2,000/month, the other for $2,500/month.

Let me tell you something: I woke up every single day for the next two months after signing those deals, convinced that I had somehow broken the law and I would find in my inbox an email saying "no, sorry, this has all been a misunderstanding, you must return to us all of that money." The process of sending an invoice of that size was surreal in a way that few things since have quite been, and more than the actual financial gain it was a deeply useful lesson in understanding that the numbers which look big to a twenty-four-year-old look like rounding errors to a sophisticated company.

The sunset

Despite all the above — an abundance of fervor and positive feedback, people willing to pay five-digit ARR sums for the data — I ended up not spending much more further time on Spoonbill. I think there were a few reasons for this.

- The product was done for my personal needs. All future development would have either been on the monetization / power-user features side (for which I didn't have much personal affinity) or for expanding into other networks (which felt somewhat boring — there wasn't clear demand for any specific network other than LinkedIn, which I was quite confident would end in a lawsuit)

- I was, frankly, distracted by shinier things: Buttondown was starting to turn the corner from "cute side project that was making some money" to "oh, I might have something here", and my work at Stripe was deep and fulfilling in a way that did not leave me with much creative energy left over at the end of the day or week.

So, I let Spoonbill sit: it continued to do its thing, albeit in a worse fashion due to the dataset growing larger and the database growing slower.

In true ouroboros fashion, someone attempted to do to Spoonbill what Spoonbill did to its predecessor, the aforementioned BioIsChanged: Flock, a YC-backed tool, joined the 2020 cohort. (Lest this sound like sour grapes — Aaron, who runs an excellent blog, reached out to ask if I was interested in partnering before he submitted his application.)

I think Flock's value proposition — a focus on CRM tooling — made a lot of sense, though it looks to be abandoned in much the same way Spoonbill is.

I think Flock's value proposition — a focus on CRM tooling — made a lot of sense, though it looks to be abandoned in much the same way Spoonbill is.

The end

And so, for the better part of three years Spoonbill sat in a pleasant stasis: it worked, it paid my mortgage, and it required zero mental bandwidth. (Whenever someone asked me about Spoonbill during those years, I would tell them with pride: the best part about it is that I could sincerely not remember the last time I had to log onto admin or make a code change.)

Then Elon bought Twitter, and they announced API changes:

lmao

lmao

This was a development best described as a bummer, even more so because the actual prices were left unannounced for many months. Once the actual API prices were announced ($42,000/month for any non-trivial amount of API traffic), it was obvious what would happen — Spoonbill would shut down.

I reached out to the remaining few customers, cancelled their recurring invoices, and scaled down the various dynos. A lovely little project had come to a lovely little end.

The epilogue

The "what if" game is easy. What if I had really gone all-in in 2018 — raised a huge round, figured out how to work with arbitrary additional networks, and so on?

Perhaps the stars would have aligned in such a way that Spoonbill would have been a huge success. The much more likely outcome, I think, is that any significant amount of product traction would have led to a series of very painful conversations with Twitter leadership.

Instead, I spent most of my time in two buckets that represent my best work to date: Buttondown and Stripe.

I think Spoonbill would have been a poor company, but it was a perfect project. I got to learn; I got to meet with people I otherwise would never have; I got to build something that people used; I got to charge money for it.

Per Stripe, Spoonbill grossed $220,300 over its lovely little existence. I'd say I spent one hundred hours on it in total (the vast majority of which came in its first few weeks, pre-launch) — so, $2,200/hour. Not bad!

Spoonbill's data sits in two places, crystalized in amber.

- A db.t2.medium RDS instance that will probably get shut down in the next year or two.

- A backup USB drive that I keep in a drawer in the desk next to me.

It's painfully rare for a piece of software to have a true sense of narrative closure: either it succeeds, and is immortal, or it is killed: killed by shifting priorities and shrunken budgets and changing macroeconomic headwinds and more exciting ideas.

Which is why I am grateful, in writing this, that I get to earn a bit of closure (even if it comes at the price of this disjointed prose — there's a reason I called this essay a eulogy!). I am very proud of what I built; I hope that, if you were a user, it brought you some small amount of insight or joy.

(Lastly, and most importantly: deep gratitude to Haley, Josh, Iheanyi, Ryan, Shep, and many more for their help and support along the way.)